Photographs that continued the peinture trouvée concept were a by-product of a working trip to Upper Bavaria. Whereas the motifs in Hildesheim in July 2017 (see Report 14/2017) were confined to the Romanesque churches, here the consistent theme was the late Baroque churches of south Germany. Given the diversity of the churches that were visited, the focus of observation lay on their common characteristics: colour, abundance and the dissolving of forms.

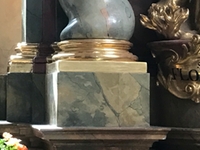

version I

(Mittenwald,

Pfarrkirche

St. Peter und Paul)

17-17-001

version II

(Benediktbeuern,

Klosterkirche

St. Benedikt)

17-17-002

version III

(Benediktbeuern,

Klosterkirche

St. Benedikt)

17-17-003

version I

(Mittenwald,

Pfarrkirche

St. Peter und Paul)

17-17-004

version II

(Murnau,

Pfarrkirche

St. Nikolaus)

17-17-005

version III

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-006

correspondence

version I

Mittenwald,

Pfarrkirche

St. Peter und Paul)

17-17-007

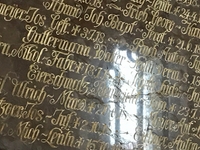

correspondence

version II

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-008

correspondence

version III

(Dießen,

Friedhofskirche

St. Johann)

17-17-009

version I

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-010

version II

(Dießen,

Friedhofskirche

St. Johann)

17-17-011

version III

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-012

version I

(Mittenwald,

Pfarrkirche

St. Peter und Paul)

17-17-013

version II

(Murnau,

Pfarrkirche

St. Nikolaus)

17-17-014

version III

(Murnau,

Pfarrkirche

St. Nikolaus)

17-17-015

direction

version I

(Andechs,

Klosterkirche)

17-17-016

direction

version II

(Murnau,

Pfarrkirche

St. Nikolaus)

17-17-017

direction

version III

(Murnau,

Pfarrkirche

St. Nikolaus)

17-17-018

version I

(Benediktbeuern,

Klosterkirche

St. Benedikt)

17-17-019

version II

(Andechs,

Klosterkirche)

17-17-020

version III

(Andechs,

Klosterkirche)

17-17-021

version I

(Andechs,

Klosterkirche)

17-17-022

version II

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-023

version III

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-024

version I

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-025

version II

(Mittenwald,

Pfarrkirche

St. Peter und Paul)

17-17-026

version III

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-027

version I

(Mittenwald,

Pfarrkirche

St. Peter und Paul)

17-17-028

version II

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-029

version III

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-030

version I

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-031

version II

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-032

version III

(Murnau,

Pfarrkirche

St. Nikolaus)

17-17-033

version I

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-034

version II

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-035

version III

(Mittenwald,

Pfarrkirche

St. Peter und Paul)

17-17-036

version I

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-037

version II

(Neresheim,

Abteikirche)

17-17-038

version III

(Murnau,

Pfarrkirche

St. Nikolaus)

17-17-039

version I

(Murnau,

Pfarrkirche

St. Nikolaus)

17-17-040

version II

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-041

version III

(Dießen,

Marienmünster)

17-17-042

On Colour in South German Baroque Church Architecture

In the eighteenth century, southern Germany developed its own culture of church building. Although this architecture belongs to the Rococo period, we hesitate to speak of Rococo churches, as the gallant, courtly, artificial element that distinguishes the spirit of Rococo is entirely foreign to south German churches of this period. In their attitude and their character they are much closer to the exuberance and love of life of the Baroque. The term “late Baroque” thus seems to us to be more suitable. It is more fitting for the period of construction and also for the character of the buildings. Nevertheless, the churches are also touched by Rococo, the style of their time. We see this both in their formal vocabulary and in colour.

A late Baroque church in southern Germany is a painted event. We experience the interiors not as painted architecture but as built painting. We stand within a three-dimensional painting. Here, space and light lose their reality. They become imaginary space and imaginary light. They become the values and criteria that determine a good painting. In this sense, when we pass through the church door, we enter a visual space whose opulence knows no frame. We can turn on our own axis ceaselessly, and still remain inside the painting and its boundlessness.

A painting is an arrangement of colour. It lives from movement and the rhythm of colour values. This also applies to the painting that appears before our eyes in the shape of a late Baroque church interior. Yet here we experience a surprise. Although we are overwhelmed, it is not the colour that overwhelms us. The colour is restrained. It remains delicate, as is appropriate for the Rococo appreciation of colour. What overwhelms us is what happens with the colour, the unfolding of the values of space and light, the abundance and the dissolution of form. An astonishing dynamic is set into motion. We recognise it as a structural dynamic, as a dynamic that penetrates and takes possession of the space. And it seems to us as if this structural dynamic were a functional opposite of the pure colour dynamic. Either the one or the other can be unleashed. Both are not possible, it seems. Only in this way can abundance arise, not chaos. It is precisely this that marks the Baroque church interior: the order that excludes chaos. The order here is so complex, so full of motion, so dynamic that here we see an extreme possibility of what order – still – can be.

Colour dynamics are thus restrained in favour of structural dynamics. However, colour dynamics also seem to give way to the differentiated dynamics of light, to a positive dramaturgy of light. Luminary effect versus colour effect would be one way to put it. Yet at the same time we experience colourism sui generis, the incomparable colourism of the eighteenth century.

An age that used architecture in order to paint thus, logically, made built volumes into an instrument to bear colour. No other century attached so little importance to the natural colour of materials. Whereas in medieval churches we perceive the stone, and in modern churches the exposed concrete as a physical reality and at the same time a colour reality, the colour dramaturgy of the eighteenth century leaves nothing to the chance result of natural colouring. Colour is subjected to strict direction, to a colour script. Colour is applied everywhere – consciously, purposefully, and always delicately. So delicately that white became a coloristic value within the ensemble.

For the artists who created ceiling paintings, the colourism of the eighteenth century was not always binding. Their palette sometimes owes more to the century of Rubens than of Watteau. This, however, only applies to the partial image space that is allotted to them. In the painted total work of art of the church interior, their coloristic impulses are above all accents that are governed by the overarching rule of colour.