At the end of August 2019 a competition proposal was submitted for a monument in Saarbrücken. This monument on Beethovenplatz in front of the synagogue is to be a memorial to approximately 2,000 people who were deported and killed under National Socialist rule. The monument is to bear their names and dates, as a substitute for a grave.

19-18-001

19-18-002

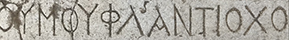

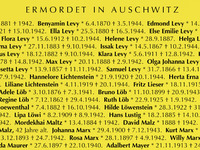

of the names

(excerpt)

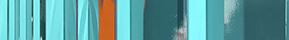

19-18-003

(photomontage)

19-18-004

(photomontage)

19-18-005

(photomontage)

19-18-006

We dig a grave in the air …

A deportation monument

The monument conveys its message on two levels:

on the sculptural and the linguistic level.

The sculptural level operates with a quote. The yellow star for Jews, a symbol of discrimination and ultimately of the cruellest persecution, has made a deep impression on the generations that followed. It is spontaneously recognised in its meaning and context. Based on this recognition, the sculpture gives a third dimension to the flat, two-dimensional Jewish star by – destructively – bending its corners. The damaged, worn-down stars lie in disorder on the ground as relics of a dreadful course of events. They seem superfluous, used, cast off. Nevertheless they are present as the last signs of life of people who have disappeared. They seem to have been thrown in the path of the following generations. Through this gesture, although they appear to lie in disorder, they amount to a coherent whole. They hold potential for movement, they seem to breathe, and they form an organism with a suggestive presence. This presence seems to be transitory. The stars hardly touch the ground – at most with their tips and edges. The massive shadows are constituent elements of the sculpture. The stars look like paper planes lying on the ground. And in their liveliness it is as if they are taking off, departing, following the people who lost them. In their gesture they still seem to be connected to the people. The floating character of the sculptural ensemble evokes associations with Paul Celan’s Fugue of Death: “We dig a grave in the air …”

The linguistic level operates with the names of the deported. These names are not merely added to the sculpture, but are themselves the sculpture. The stars, regardless of their own autonomous symbolism and sculptural gestures, are shown to be first and foremost the bearers of the names. They rise diagonally like lecterns to present the names to the gaze of the reader and viewer. The plurality of stars stands for the plurality of places of death. Auschwitz alone requires two stars. On other stars, several sites of death are brought together. In this way the names tell a story, the story of deportation, which ends at numerous places of death via transports across Europe. The sorting of the names according to the place of death creates links, communities of fate in death. For today’s public, this supplies historical information: where was that? And how many died there? The places of death form typographical units. Where several different places are subsumed in one typographical unit (e.g. “murdered elsewhere in Poland”), the individual place of death is given after each name. The names have a different font style than the dates of the persons’ lives. This lends dynamism to the typographical units. They seem to be amorphous organisms. Moreover, the free alignment of the script dissolves the external contour. The typography provides an association with clouds. Within these clouds of type and name, the eye moves easily from name to name, from person to person. The alphabetical order makes it easier to find individual names. The beholder passes between the stars as between the graves in a cemetery, with the star-shaped “lecterns” pointing in all directions. There is no front and back, no beginning and end. There is only a concentration in the middle, where the stars are closer together and bear the largest “name clouds”. The space in front of the synagogue becomes a place of gravestones that are evidently not gravestones, as the sculptural gesture refers to the grave in the air.